|

| Y |

esterday’s Wall Street Journal reported that Kodak was preparing to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection if it couldn’t raise cash by selling 1100 of its digital imaging patents. This caught me by surprise, but it shouldn’t have.

I lived in Rochester, NY during the 1960s and had many friends who worked at Kodak (“The Big Yellow Mother”). It was the industrial backbone of a city that was loaded with technology leaders: General Dynamics, Xerox, General Motors, Bausch & Lomb, General Railway Signal, Gleason Gear, Stromberg-Carlson, RF Communications. Kodak’s main office on State Street alone employed 35,000 people

It seemed that the party would never end. Kodak was built upon the same business model as Gillette razor blades: give away the camera in order to make money on the consumables (film and paper). It had missed some golden opportunities when it turned away new technologies offered by inventors Edwin Land (Polaroid instant photography) and Chester Carlson (Xerox copying), but the party continued, fueled by juicy film and paper revenues.

|

Smart manufacturing kept camera prices low

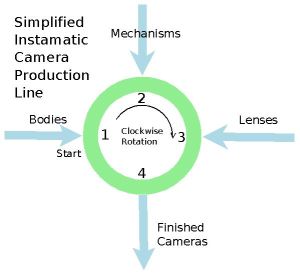

Kodak had some brilliant engineers on board. Around 1969 I visited its Instamatic camera production facility. It was impressive. The camera was assembled entirely by machine on a circular assembly line. Each segment of the circle was fed by a spoke that transported sub-assemblies inward to the assembly line. Parts were picked and moved from inventory via robotic pickers/carts.

The plastic lenses were (injection?) molded by computer-controlled presses that used multi-cavity molds. Each lens was light-beam tested under computer control and statistics kept on the percentage of rejects produced by each mold cavity. When the percentage of rejects from a particular cavity exceeded a limit, that mold cavity was replaced during the next scheduled downtime.

I was told by my host that Kodak knew that Japanese manufacturers were nipping at its heels, so they invested heavily in the latest low-cost manufacturing techniques. I was told that most of the manufacturing engineering was done in-house.

I was impressed with what I saw and was sure that Kodak had a bright future.

|

Invents the digital camera

In the mid-1970s, Kodak experimented with CCDs (Charge Coupled Devices), which are light-sensitive solid-state devices. They developed a prototype digital camera around 1975-76. Krista Gleason wrote about it in her two-part 2008 article, titled A Kodak Moment with Steve Sasson. In the article, Steve describes the tough time he and two technicians had developing the camera, which eventually captured a full image in December 1975.

Sells camera manufacturing to Singapore

I’ve lost touch with Kodak and am not an active photographer. However, it seemed to me that Kodak was competing successfully in the new world of digital imaging. I guess that I was wrong. In view of the advanced camera manufacturing that I’d witnessed decades before, I was surprised to learn that Kodak had sold its camera manufacturing operations to Singapore-based Flextronics in 2006.

Today Kodak is concentrating on the inkjet printer market. I’m not surprised: inkjet consumables are way overpriced. Some inkjet ink, if purchased in gallon containers, would cost thousands of dollars per gallon. Unfortunately, it’s a crowded market and Kodak is way behind first-place. (Besides, inkjet printers make lousy copies.)

It’s sad to see a once proud giant brought low.

Good article!

It is a shame that Kodak has done so poorly in recent years after being an innovator for so many years.

What is surprising is that Rochester is doing as well as it is, given the national economy and the decline of both Kodak and Xerox. However, there are many good colleges in the area, still cranking out graduates. It’s great to see that entrepreneurs have filled what could have been a chasm and that innovation (apparently without much government help) still prevails there.

Recently, the WSJ ran this article:

Rochester, the New York home of Eastman Kodak Co., ticks many of the standard Rust Belt boxes.

Crumbling corporate benefactor? Check. Acres of vacant lots? Check. Soaring unemployment? Well, no.

Even after a quarter century during which Kodak wiped out nine of every 10 jobs it had in the city, greater Rochester’s jobless rate is running well below the national average—at 7.3% in October, the most recent available, compared with a national rate of 9% at the time.

Rochester has managed this feat with a resurgence of entrepreneurial activity that has filled the void left by its shrinking corporate giants, among them Kodak, Xerox Corp., Bausch & Lomb Inc. and General Motors Co.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204336104577092313580006528.html

LikeLike

That’s an interesting article and judging by a couple of its comments, may be an attempt to paint a happy face on a sad situation. (One critic elsewhere said that the laid-off engineer turned “entrepreneur” was merely “selling off his house’s belongings”.)

There was a productive synergy between Rochester’s technology-based businesses and the University of Rochester (UofR) and more recently Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT). Both schools provided skilled employees and platforms for research. A colleague at RF Communications taught graduate Electrical Engineering courses at UofR at night just for fun. It was that sort of community.

With all of those technical resources, it’s hard to imagine that Kodak’s gone off the rails. I suppose that Kodak’s management and board of directors for the past 3 decades must take nearly all of the blame. This may be a lesson that when you sense that there’s a new technology on the horizon, you immediately embrace that new technology. Ignore it and it may run right over you.

.

LikeLike

The plot thickens!

Eastman Kodak Co. sued mobile phone and tablet makers Apple Inc. and HTC Corp. for patent infringement on Tuesday.

The lawsuits, which were filed in federal court in Rochester, N.Y., relate to a series of patents for transmitting digital images from cameras and other devices.

http://blogs.wsj.com/law/2012/01/10/smile-kodak-takes-shot-at-apple-htc-in-patent-fight

LikeLike

Again, the whole question of inellectual property (IP) arises. The first two comments to the WSJ article denounce the whole idea of patents.

I recently wrote about Acoustic Research founder Edgar Villchur and his decision to avoid pursuing his patent rights. He in turn referred to Edwin Armstrong’s sad and brutally expensive legal and commercial odyssey while defending his patents against RCA and other major corporations.

I have no fixed opinion on IP. One day I sympathize with one side; the next day I sympathize with the other side.

LikeLike

NYT article today about Rochester being a “job-growth leader” in NY:

It feels like the wrenching culmination of a slide over decades, during which Kodak’s employment in Rochester plummeted from 62,000 in the 1980s to less than 7,000 now. Still, for this city in western New York, the picture that emerges, like a predigital photograph coming to life in a darkroom, is not a simple tale of Rust Belt decay.

Rochester has been a job-growth leader in the state in recent years. In 1980, total employment in the Rochester metropolitan area was 414,400. In 2010, it was 503,200. New businesses have been seeded by Kodak’s skilled work force, a reminder that a corporation’s fall can leave behind not just scars but also things to build upon.

“The decline of Kodak is extremely painful,” said Joel Seligman, president of the University of Rochester, which, with its two hospitals, is the city’s largest employer with 20,000 jobs. “But if you step back and look at the last two or three decades, you see the emergence of a much more diversified, much more knowledge-based economy.”

Rochester’s troubles go beyond Kodak. Xerox and Bausch & Lomb have shed thousands of jobs as well. Twenty-five years ago, the three companies employed 60 percent of Rochester’s work force. Today, it is 6 percent.

The most painful toll is in the city itself, where the population has dropped to 210,000 from a peak of 332,000 in 1950, and where vast stretches north of downtown are dreary acres of decay. And while job growth has been strong, wages have declined from well above the national average at Kodak’s peak to below it now, reflecting the dwindling of well-paying factory jobs.

There are some good comments, including this one — reminds one of building better buggy whips when automobiles appeared:

Unfortunately, as when the railroads ignored the arrival of the airplane as the new paradigm of transportation, Kodak continued to think that they were in the film business rather than the image business. Had they moved into digital imaging I believe they would have remained an unstoppable juggernaut.

And another:

Kodak Park was so big it had its own internal highway system, rail system, fire departments and miriad cafeterias and health centers. What happened? Even as a college student working there in the summer in the 70’s it was not hard to see that management was more interested in their own climb up the ladder, that new market ideas were considered a risky threat to career advancement and that falling in line with status quo was what got one to the top job. Basically a corporate repeat of what happened to General Motors. It takes time to kill a great company and promotion by sycophancy was the cancer that has just about marginalized Kodak to death.

LikeLike

Good article. I’m not sure that the decline of Rochester’s population is unique. Didn’t most cities’ core populations decline over the same period? On the other hand, I wonder about the population change in Rochester’s suburban communities such as Brighton, Pittsford, Fairport, et al? I wonder if they absorbed the population that Rochester itself lost.

Unlike General Motors (which should have been allowed to close its doors), it’s unlikely that Mr. Obama will try to rescue Kodak with taxpayer money. Kodak kept unions out by treating its workers to excellent wages and working conditions, so Kodak offers no union votes to be purchased with taxpayer money.

LikeLike

Not so fast on GM….

GM becomes world’s top selling automaker in 2011

(Reuters) – General Motors Co reclaimed its title as the world’s top selling automaker for the first time since 2007, after sales of more than 9 million vehicles globally in 2011. GM’s return to the top slot comes more than two years after its taxpayer-funded bankruptcy restructuring that allowed the Detroit-based automaker to cut its spiraling legacy costs. GM vaulted to the top spot last year for the first time since 2007.

LikeLike